HMM-162 Events Diary

We were a peacetime Marine Helicopter Squadron operating out of the Marine Corps Air Station, New River, North Carolina. The big war in Vietnam was over and we were training new maintenance personnel and pilots for future wars. Many of our younger Vietnam veterans had returned to civilian life. The Squadron's

I think Maintenance Officers are chosen for their energy level and knowledge of mechanics. A Squadron Maintenance Officer is a senior pilot in the Squadronís Table of Organization. This is a leadership position for career advancement purposes and it also provides the Maintenance Department with a dedicated test pilot. Our Maintenance Officer was Major Dennis Churchin, a typical outstanding Marine Maintenance Officer with all the necessary qualifications for that position. He would fly an aircraft until all of its discrepancies were identified and repaired. He needed to be slow and methodical making safety of flight decisions, but produce operational aircraft as fast as possible. Major Churchin had the experience to do his troubleshooting right and the personal drive to keep at it until the job was done. He was the right person at the right time for this Squadron. Everyone liked and respected our Maintenance Officer including the troops.

We had several pilots that possessed high levels of personal courage. They were fearless in some difficult situations. When a pilot has a problem inside or outside the aircraft, an exceptional pilot evaluates the problem in a cool and calm manner and comes up with the right solution. We normally think of courage as a personal trait that military people demonstrate during combat. Some pilots are brave individuals that fight and succeed in the difficult environment of weather, terrain and the flight limitations of helicopters. If your machine is failing for some reason, the person in the driver's seat makes the difference between life and death. When a pilot puts his responsibilities before his mortality or the normal fear we all feel, everyone on the aircraft is more likely to survive. Some of our pilots had been flying helicopters for many years. They could fly their manchine without being occupied by some of the unimportant details involved in its basic operation. They knew what was important and they had the all-important feel for the machine. Major Churchin and several other Squadron pilots had high levels of personal courage and they were skilled pilots.

A benefit of the Vietnam conflict was that Marine Corps Aviation had some very experienced maintenance personnel. All of our Non Commissioned Officers were experienced veterans. Some had been working on the CH-46 for almost a decade. Marines with that type of experience in a leadership position are what we needed to be a successful Maintenance Department. We had some great Non Commissioned Officers.

Most Squadron Maintenance Departments have about 150 individuals.

The 46 fleet was going to be in a down status until every rotor blade could be inspected. There are three ways to inspect rotor blades spars. Ultrasound, x-ray and dye penetrate. Dye penetrate wouldnít work because the blade would need to be disassembled for inspection. X-ray inspection equipment couldnít handle the spar length in the field. An Ultrasound inspection of every blade appeared to be logical solution to the problem. A group of civilian technicians from the Naval Rework Facility in Norfolk were tasked with doing ultrasound inspections on all CH-46 rotor blades on the East Coast. We had about 100 helicopters on the ramp at New River without rotor blades. What do you do when you canít fly? We were going to do classroom training for the pilots and Maintenance Department personnel. We called it a Safety Stand-down. After removing all those blades, it was time to take a break.

After all of our blades were inspected, we reinstalled the blades and flew again. The permanent fix for the blade problem was to install a pressure indicator at the root of the spar. Each spar was pressurized and a go/no go indicator was checked on every preflight. Sikorsky aircraft had been using a similar vacuum system on their spars for years. If you had a bad indicator, you had a crack and the aircraft was down until the blade was replaced. CH-46 aircraft today are flying with composite blades. The old blades with the aluminum spars and the composite leading and training edge are gone. I think we wore them out in Vietnam.

Our Crew Chiefs were going to be the secret to our success. Each Crew Chief owns a specific aircraft and they call it their aircraft. A Crew Chief is responsible for most of the mechanical maintenance done on his or her aircraft. They also lobby all the other shops for the non-mechanical work that has to be done on their aircraft. In a different squadron, I once had a Crew Chief tell me that he was going to break my nose if I didnít ask permission before I did work on his aircraft. We later became good friends and my nose was already broken. If your Squadron has motivated Crew Chiefs, your maintenance effort is going to be successful. They do the heavy lifting, put in the long hours and they really do own their aircraft. The rest of us are just along for the ride.

It was time to make a composite squadron and go on a cruise. We needed 4 AH1J, 2 UH1N and 4 CH-53D aircraft beside the standard 12 CH-46D aircraft we already had in our inventory. We would do some carrier qualifications off the coast of North Carolina with the USS Iwo Jima, check their supply system, maintenance spaces and the most important thing, their food.

The AH1J and UH1N aircraft were almost new and they came with those great T400 power pack engines. The only problem with new aircraft is the tools and replacement parts may not be available aboard ship. Outfitting a ship with new aviation maintenance tools and parts lag new aircraft development by about a year. We did find some replacement parts for a F4U Corsair during a prior cruise on the USS Boxer. The CH-53D was the same aircraft that we had been flying for several years and they were doing a great job We had a service bulletin that warned us about a corrosion problem in the rear ramp area. We did the inspection and continued with our deployment planning. Both detachments looked good. We needed to select the best 12 CH-46D aircraft and transfer the rest. We were going to on-load at the dock in Moorhead City, North Carolina. The ship was tied to the dock in the turning basin below the bridge. The dock was next to a 65-foot high rise bridge that crossed the Inter Coastal Waterway. We had a lot of ground support equipment for the different types of aircraft and moving all that gear down the highway would be a big job.

The aircraft and the Squadron personnel would embark by air. We would start flying to the ship by 0900 hours and should be safely aboard by noon.

We didnít fly much going across the big pond. We were in a hurry and we didn't know why at the time. We did a modest amount of carrier qualifications for the pilots. We didnít have any maintenance problem because the flight schedule was super small. We arrived at Rota, Spain to do whatever ships do in Rota. We didnít fly while we were there. After about 3 days in Rota, we packed up and moved out for Naples, Italy. We flew some on the way to Naples, but not much. We found a dead man floating in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea. He had black socks on his feet and nothing else. We fished him out of the sea and he went to Naples with the ship. I think he became a European John Doe. The port of Naples is a beautiful place. We were anchored in the harbor and the Italians were sailboat racing between us and the shore. We had a ringside seat for the activities. Liberty was expensive because the exchange rate was not in our favor.

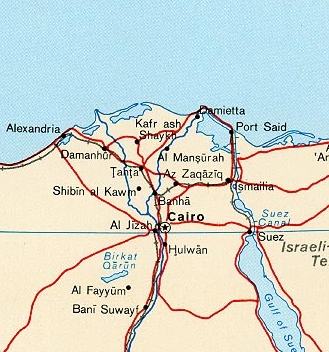

Naples was the headquarters for the 6th Fleet and we were getting our marching orders. After 4 days at anchor, we departed Naples to join with other military units from all over the world to remove the mines and other ordinance from the Suez Canal. We were going to be part of a coalition of nations.

We arrived off of Port Said,

The Navy was working very hard with their old aircraft. They were burning the midnight oil on the hangar deck almost every night. They were making good progress with the mines in the Canal and the lakes surrounding the Canal. We were doing our logistics mission between our ships and the surrounding airfields. We did have one major problem. We had aircraft parked on both sides of the paved road at Ismailia. A pilot would taxi between the parked aircraft and take off at the end of the paved road. We had one CH-46D taxi down the road and make blade contact with two other aircraft parked on both sides. Three aircraft down and 5 blades damaged and we didnít have any spare blades. We could cannibalize the blades from an aircraft on the boat and get our damaged aircraft back to the ship, but one of our aircraft on the boat would become a hangar queen. Rotor blades were in short supply throughout the supply system because of the crack problems we encountered at New River.

We pulled liberty in Cairo while we were anchored at Port Said. A boat ride to Port Said and then a 100 miles bus ride to Cairo. A round trip was one day going and one day coming back.

After a good liberty in Alexandria, it was time to go back to work.

Two of our allies, Greece and Turkey were thinking about going to war over the island of Cyprus. Cyprus was an island divided into two separate ethnic factions. The problems on the island could create a war on the mainland between Greece and Turkey. Both countries had NATO nuclear weapons positioned on their soil manned by American military personnel. The security of these weapons could be in jeopardy if they went to war. We were going to practice moving nuclear weapons with our CH-53D aircraft in case they started a shooting war. With our CH-53D on the flight deck, we loaded and unloaded dummy weapons. You couldnít close the rear ramp door with the big missile on board, but being inside the aircraft was better than hauling it as an external.

We were back to carrier qualifications and doing load and unload exercises with the Battalion. The aircraft were holding up well and everyone was flying. We had one case where the ship had to rebuild a rotor head for an AH1J and the Crew Chief didnít like the way it looked. One of the rings in the swashplate was loose. After a careful examination, we determined that it was installed backwards and upside down. We let the ship do that rebuild again. The AH1J and UH1N aircraft were almost new and they were almost trouble free. The CH-46D aircraft were all flying well and we had a talented group of experienced pilots and maintenance personnel. The CH-53 detachment personnel had to go through losing an aircraft and their shipmates. It took awhile but they recovered. Integration of all the maintenance personnel within a composite squadron takes time and effort. There is a point that all detachments blend into the Squadron Maintenance Department as a whole. They become stronger and more capable when this happens. It happened to us after the CH-53 accident and the AH1J rotor head problem. After another liberty in Naples, it was time to do an amphibious landing in Spain.

Our amphibious assault was a big deal for us and we didnít have any aviation problems and no accidents. The cruise was looking pretty good. We did have a CH-53D main transmission that was making metal. A chip detector would go off and the detector would have a few shaving on it and that was all. We took off the bottom inspection port and we didnít see anything unusual. We decided to fly it and see what happen. About an hour into the next flight, the chip detector fired the warning light again. The transmission had more shaving on the chip detector. The transmission was making metal and we couldnít tell where it was coming from. We were going to need a new transmission. The Squadron was down to two CH-53D aircraft and one hangar queen. Could we get a transmission before the off load at Moorhead City? It didnít look good. The ship anchored off the heel of Italy and we did some cross-country flying to Naples and other destinations in Italy. Out of the blue, we received a CH-53 transmission. The shipís aircraft carried the transmission to us as an external lift. Aircraft availability was looking better. Somewhere along the line someone had made a mistake. The transmission that we received was a bad transmission that should have been going to a repair facility stateside. We did a lot of work for nothing and we still needed a transmission. We were having one of those bad days.

Another practice procedure was to load the Battalion and fly them to a set of coordinates at sea and then return to the ships. That procedure tested the launch and recovery timing for the Ships, Squadron, and the Battalion. We had one CH-46D that lost an engine with a full load of Marines about 50 miles from the Iwo.

We were too close to going home to get another CH-53 transmission. A few liberty ports and a stop at Rota, Spain and we were history. In the old days, we would fly ashore as we approached the States, get the part we needed and fly back to the ship. The down aircraft would fly a test hop home with the new part installed. A CH-53D is too big and too complicated to do that type of maneuver. We would be using a crane to off load our down CH-53D at the dock.

All but one of our aircraft launched for home while the ship was still off the coast of North Carolina.

We had to transfer our detachment aircraft back to their parent Squadrons at New River. It was time to get out of the composite squadron mode of operation. We didnít like to see them go, but thatís the way the system works. I think the detachments were glad to get back home to tell their stories. We needed to accept some new aircraft from the Group pool of aircraft and get back up to 18 aircraft. We were transferring some of our maintenance personnel and getting some new people as soon we arrived home. Thatís the way Marine Corps Aviation works. We would be back in the training business again after getting some new aircraft and some new personnel. The aircraft at New River still had a shortage of rotor blades because most of the overhauled blades were going to tactical units afloat. We were in good shape because our original 12 shipboard aircraft had blades. The new aircraft that came from the pool didnít have blades. We were going to be back in the business of removing and replacing rotor blades for awhile.

Everything was working pretty well in our new training environment until we had an accident on the ramp. One of our CH-46D came apart on the ramp and destroyed itself on shutdown. We had one dead pilot and 2 injured crew members. The pilot had flown to a ship off the coast and done some touch and go landing and then returned to New River. After landing, he taxied through the refueling point, the deluge system and then taxied to a parking spot on the ramp. He did a normal shutdown by bringing the engine quadrant back to the start position and applying the rotor brake. At that time, the rotor system became uncontrollable and the copilot released the rotor brake and advanced the engine quadrant control back to the fly position. The aircraftís rotor system cut the fuselage in half. The rotor blades were broken into several pieces killing the pilot.

What went wrong? The National Transportation Safety Board sent an inspector and he evaluated the mechanics of the aircraft. He looked at the drive shaft, rotor heads, swashplates, pitch links, transmissions, actuators, rotor blades and anything else that might have caused the accident. He couldnít find anything wrong, but something caused the accident. Aircraft donít come apart on the ramp for no reason. All the damaged pieces were in the hangar next to our hangar and those pieces were going to tell us what happen. When a rotor blade breaks, the bonded leading edge and the bonded trailing edge will break where the spar breaks. We had five examples of this type of breakage on the floor in front of us. We also had one other blade that didnít break like the other blades. The leading edge was broken in pieces, but not at the same location on the spar. In fact, the leading edge of that blade was not bonded to the spar at all. Why did all the rotor blades break into composite pieces except for that one blade? Did we have find the cause of the accident? I think we did.

The Navy Rework Facility at Cherry Point, North Carolina was busy with the overhaul of CH-46 rotor blades.

Why didnít the blade fail when the aircraft was on its test hop after a blade change? It did; this was the test hop, track the rotor blades and go. The pilot was a qualified test pilot. This was the first time the aircraft had shut down after the new rotor blade was installed. Could the accident have been prevented? Of course it could. Almost every aircraft accident is the result of human error. Once our bad rotor blade was overhauled and issued as air worthy, someone was going to have an accident. Poor supervision at Cherry Point caused the accident.

Reading about real aircraft accidents can be a valuable tool. We all know that if we touch a hot stove, we are going to burn our fingers.

Helicopters are unusual aircraft. They can't fly like birds and they don't glide like a fixed wing aircraft. They have lots of mechanical parts that are all going in different directions at the same time. They are not very graceful in flight and they make lots of noise. On the other side of the coin, Marine Corps helicopters are some of the most versatile machines ever built. As a military force, we would have a difficult time performing our mission without helicopters. Marine Corps helicopter aviation has some of the best pilots and maintenance personnel in the World. Flying a complicated machine in poor weather and in and out of rough terrain is a normal dayís work for most Marine Corps Squadrons. Making the machines safe and available is the mission of the Maintenance Department.

Maintenance Department

1973 to 1975

Non Commissioned Officers were Vietnam veterans with lots of experience and they would be the backbone of our maintenance effort. We were in the original ďNew HangerĒ at New River with lots of space and air conditioning. The offices and the pilotís ready room were on the upper deck and the maintenance spaces were down below on the hanger deck. We had 18 CH-46D aircraft and they were in good condition.

Non Commissioned Officers were Vietnam veterans with lots of experience and they would be the backbone of our maintenance effort. We were in the original ďNew HangerĒ at New River with lots of space and air conditioning. The offices and the pilotís ready room were on the upper deck and the maintenance spaces were down below on the hanger deck. We had 18 CH-46D aircraft and they were in good condition.

Most of our Marines were learning the business of aircraft maintenance. They graduate from a formal technical school and then continue with their hands on training in an operational Squadron. Individual Marines need both types of training. Being a good student in a formal school provides the logic to be a good troubleshooter. If a maintenance person understands how a system is suppose to operate, he or she can identify a problem and then remove and replace the right component until the system operates correctly. It sounds simple, but some helicopter systems are very complicated. Waiting 30 days for a part that doesnít fix the problem can kill aircraft availability. Most of our junior maintenance personnel were very good and we knew they were going to get better. Our deployment to the Mediterranean Sea would change our status from a training mission to a force in readiness at sea.

Most of our Marines were learning the business of aircraft maintenance. They graduate from a formal technical school and then continue with their hands on training in an operational Squadron. Individual Marines need both types of training. Being a good student in a formal school provides the logic to be a good troubleshooter. If a maintenance person understands how a system is suppose to operate, he or she can identify a problem and then remove and replace the right component until the system operates correctly. It sounds simple, but some helicopter systems are very complicated. Waiting 30 days for a part that doesnít fix the problem can kill aircraft availability. Most of our junior maintenance personnel were very good and we knew they were going to get better. Our deployment to the Mediterranean Sea would change our status from a training mission to a force in readiness at sea.

The food situation for the troops and the Non Commissioned Officers looked good. After checking out the Officer's mess, it appeared that the officers were going to lose weight on this cruise. I had sailed on this ship several years before off the coast of Vietnam. We would have a different crew and a different support system. Our supply depot at Subic Bay wouldnít be around the corner and the Marine Corps was cutting expenditures after Vietnam. Getting on the boat wouldnít be a problem, but I was already worried about getting off the boat when the cruise was over.

The food situation for the troops and the Non Commissioned Officers looked good. After checking out the Officer's mess, it appeared that the officers were going to lose weight on this cruise. I had sailed on this ship several years before off the coast of Vietnam. We would have a different crew and a different support system. Our supply depot at Subic Bay wouldnít be around the corner and the Marine Corps was cutting expenditures after Vietnam. Getting on the boat wouldnít be a problem, but I was already worried about getting off the boat when the cruise was over.

The ship was scheduled to depart that afternoon. We would sail with the tide. The Squadron launched from New River in groups of 4 aircraft each. That made for a reasonable recovery interval at the other end. The aircraft had to land, off load passengers, fold blades and then move to a storage area on deck. A four aircraft launch worked well. The last aircraft on board was a CH-46D flown by our Maintenance Officer, Major Churchin. The Iwoís flight deck was crowded and landing wasnít going to be easy. The wind was blowing in from the ocean and the Iwo was sitting tied to the dock with her bow almost into the wind. Major Churchinís 46 dropped down next to the high- rise bridge missing some power lines and then landing ever so lightly on that little open spot on the flight deck. Some of people in the back of the aircraft could have talked to the people in the cars on the bridge if we had less noise. Major Churchin's aircraft was heavy during that landing and we looked good. Everyone made it on board and we were ready to leave for the Mediterranean Sea and our big adventure.

The ship was scheduled to depart that afternoon. We would sail with the tide. The Squadron launched from New River in groups of 4 aircraft each. That made for a reasonable recovery interval at the other end. The aircraft had to land, off load passengers, fold blades and then move to a storage area on deck. A four aircraft launch worked well. The last aircraft on board was a CH-46D flown by our Maintenance Officer, Major Churchin. The Iwoís flight deck was crowded and landing wasnít going to be easy. The wind was blowing in from the ocean and the Iwo was sitting tied to the dock with her bow almost into the wind. Major Churchinís 46 dropped down next to the high- rise bridge missing some power lines and then landing ever so lightly on that little open spot on the flight deck. Some of people in the back of the aircraft could have talked to the people in the cars on the bridge if we had less noise. Major Churchin's aircraft was heavy during that landing and we looked good. Everyone made it on board and we were ready to leave for the Mediterranean Sea and our big adventure.

The Iwo Jima would be the floating airfield for the Suez Canal mine sweeping operation, Nimbus Star. We were going to embark special mine removal aircraft that the Navy owned from the Naval Air Station at Sigonella, Sicily and we needed a solution for the space problem on the ship. It was going to be crowded. Our Squadron had 22 aircraft and the Navy wanted to operate a bunch of very large CH-53A aircraft off the same deck. Something had to change if the mine sweeping mission was going to work. They needed almost all the flight deck and maybe half the hangar deck for their operations. Our Squadron mission was to provide support for the Navyís mission during the Suez Canal operation and the first requirement was for us to get out of the way. The solution was to send some of our aircraft to the other amphibious ships in our flotilla and park them until the Navyís mission was complete. Some of our aircraft would be in storage for the duration of the Suez Canal mission. We shared our maintenance and operations spaces with the Navy and helped them when we could. We flew into Crete on our way to the Suez Canal and had a liaison meeting with the British. They have a small airfield and a barracks on the Island. We were invited to lunch and it was excellent. You shake hands with the British and they invite you to eat lunch, tea or supper. The British have very good manners. I have been eating with them all over the world for very long time.

The Iwo Jima would be the floating airfield for the Suez Canal mine sweeping operation, Nimbus Star. We were going to embark special mine removal aircraft that the Navy owned from the Naval Air Station at Sigonella, Sicily and we needed a solution for the space problem on the ship. It was going to be crowded. Our Squadron had 22 aircraft and the Navy wanted to operate a bunch of very large CH-53A aircraft off the same deck. Something had to change if the mine sweeping mission was going to work. They needed almost all the flight deck and maybe half the hangar deck for their operations. Our Squadron mission was to provide support for the Navyís mission during the Suez Canal operation and the first requirement was for us to get out of the way. The solution was to send some of our aircraft to the other amphibious ships in our flotilla and park them until the Navyís mission was complete. Some of our aircraft would be in storage for the duration of the Suez Canal mission. We shared our maintenance and operations spaces with the Navy and helped them when we could. We flew into Crete on our way to the Suez Canal and had a liaison meeting with the British. They have a small airfield and a barracks on the Island. We were invited to lunch and it was excellent. You shake hands with the British and they invite you to eat lunch, tea or supper. The British have very good manners. I have been eating with them all over the world for very long time.

Egypt and dropped the hook. Port Said is at the mouth of the Suez Canal in the Mediterranean Sea. The weather was hot and humid and we didnít have any wind. The Navy started their program of mine removal. We established a base of operations half way down the Canal at Ismailia, Egypt. Ismailia was the headquarters for the Suez Canal Authority at that time. It had a few trees, a paved road, a two-story building and a few out buildings. The paved road would be our airfield and the two-story building would be our headquarters at this remote site. We could park a few aircraft there and they would be off the ship and out of the way. Land mines were everywhere. You couldnít walk anywhere except in designated areas that had been cleared of mines. An aircraft making an emergency landing on either side of the Suez Canal would have been in trouble. If you didnít hit a mine when you landed, you still couldnít leave the aircraft on foot after landing. The houses between Port Said and Ismailia didnít have roofs. Most of them had four walls and some of them were occupied. It doesn't rain in the dessert or maybe they didnít need a roof? I think the real reason was that the owners had removed the roofs when they evacuated the area. They had to leave during the war or die. Roof materials are very valuable in the dessert and I think they took their roofs with them when they fled the area.

Egypt and dropped the hook. Port Said is at the mouth of the Suez Canal in the Mediterranean Sea. The weather was hot and humid and we didnít have any wind. The Navy started their program of mine removal. We established a base of operations half way down the Canal at Ismailia, Egypt. Ismailia was the headquarters for the Suez Canal Authority at that time. It had a few trees, a paved road, a two-story building and a few out buildings. The paved road would be our airfield and the two-story building would be our headquarters at this remote site. We could park a few aircraft there and they would be off the ship and out of the way. Land mines were everywhere. You couldnít walk anywhere except in designated areas that had been cleared of mines. An aircraft making an emergency landing on either side of the Suez Canal would have been in trouble. If you didnít hit a mine when you landed, you still couldnít leave the aircraft on foot after landing. The houses between Port Said and Ismailia didnít have roofs. Most of them had four walls and some of them were occupied. It doesn't rain in the dessert or maybe they didnít need a roof? I think the real reason was that the owners had removed the roofs when they evacuated the area. They had to leave during the war or die. Roof materials are very valuable in the dessert and I think they took their roofs with them when they fled the area.

Everyone caught the Pharaohís revenge on liberty. Americanís hadnít been in Egypt for 20 years and we couldnít handle the bugs in the water. Some people were sick enough to be evacuated stateside. We had some pills issued by the Shipís Sickbay that helped the situation. We were concerned about having enough people to fly a flight schedule. The Navy finished the mine sweeping job and it was time to celebrate. This was a high level project and President Nixon was on his way to Egypt to talk politics with President Sadat. We were going to support President Nixonís visit to Egypt. The Navy launched one of their aircraft to the Alexandria International Airport with our Ambassador to Egypt. As the aircraft taxi towards the terminal, a main rotor blade hit a flagpole in front of the terminal. We were having another bad day with rotor blades and moving aircraft on the ground. When an H-53 main rotor blade hits a solid object, the tail pylon falls off the aircraft. Sudden stoppage between the main rotor system and the tail rotor system twist the tail off the aircraft. This type of damage canít be fixed in the field. The aircraft had to be pulled by a tractor on a long road trip from Alexandria's International Airport to Cairo's International Airport for a short trip home on a C5 aircraft. Our ship was on its way from Port Said to Alexandria. We were going to be dockside in Alexandria for liberty. President Nixon and his group of diplomats needed our anti-diarrhea medicine. The President had priority for the pills and we were going to be on our own. Everyone had to remember; donít drink the water.

Everyone caught the Pharaohís revenge on liberty. Americanís hadnít been in Egypt for 20 years and we couldnít handle the bugs in the water. Some people were sick enough to be evacuated stateside. We had some pills issued by the Shipís Sickbay that helped the situation. We were concerned about having enough people to fly a flight schedule. The Navy finished the mine sweeping job and it was time to celebrate. This was a high level project and President Nixon was on his way to Egypt to talk politics with President Sadat. We were going to support President Nixonís visit to Egypt. The Navy launched one of their aircraft to the Alexandria International Airport with our Ambassador to Egypt. As the aircraft taxi towards the terminal, a main rotor blade hit a flagpole in front of the terminal. We were having another bad day with rotor blades and moving aircraft on the ground. When an H-53 main rotor blade hits a solid object, the tail pylon falls off the aircraft. Sudden stoppage between the main rotor system and the tail rotor system twist the tail off the aircraft. This type of damage canít be fixed in the field. The aircraft had to be pulled by a tractor on a long road trip from Alexandria's International Airport to Cairo's International Airport for a short trip home on a C5 aircraft. Our ship was on its way from Port Said to Alexandria. We were going to be dockside in Alexandria for liberty. President Nixon and his group of diplomats needed our anti-diarrhea medicine. The President had priority for the pills and we were going to be on our own. Everyone had to remember; donít drink the water.

We needed to get rid of the Navy Mine Sweepers and get our aircraft back on board. A short sail to Sigonella, Sicily and we off loaded the Navy aircraft. The Navy Supply system found the rotor blades we needed for our CH-46 aircraft. We picked up enough replacement blades at Sigonella to make our hangar queen operational. We were pleasantly surprised. It was time to move all of our displaced aircraft back to the Iwo and for us to get on with our primary mission. All the maintenance spaces on the boat became larger. We had more space with fewer people. Life was better on the boat.

We needed to get rid of the Navy Mine Sweepers and get our aircraft back on board. A short sail to Sigonella, Sicily and we off loaded the Navy aircraft. The Navy Supply system found the rotor blades we needed for our CH-46 aircraft. We picked up enough replacement blades at Sigonella to make our hangar queen operational. We were pleasantly surprised. It was time to move all of our displaced aircraft back to the Iwo and for us to get on with our primary mission. All the maintenance spaces on the boat became larger. We had more space with fewer people. Life was better on the boat.

They didnít go to war and we didnít have to evacuate our nuclear weapons. The war of words on the Island was getting hotter and we needed to evacuate our nationals and anyone else wanting to leave the Island. We picked up a bunch of people with all their possessions and transported them to Israel. We flew them into Tel Aviv and then returned to a standby status sailing off the coast of Italy. All of our aircraft were in an up status and we were scheduled for an amphibious landing in Spain in a few weeks. For the present, we could practice night externals with the CH-53D. The plan was to pick up a 105-millimeter howitzer off the stern of our flotilla Landing Ship Dock at night, fly a circle and then deposit it back on the same deck. The Squadron would maximize the available flight time by hot seating pilots. The aircraft carried a crew of two pilots, one crew chief and one gunner. They also carried two more sets of pilots for the hot seat operation. Each set of pilots picked up the howitzer and put it back on the shipís deck. Night externals appeared to be a success. When the drill was finished, the aircraft was going to take off and fly back to our ship. The aircraft departed the LSDís flight deck without a problem and then flew into the water. We lost 4 people in that crash and we didnít do any more night externals. Night vision capability didn't exist at that time. The purpose of the training was for a night amphibious landing that never happened.

They didnít go to war and we didnít have to evacuate our nuclear weapons. The war of words on the Island was getting hotter and we needed to evacuate our nationals and anyone else wanting to leave the Island. We picked up a bunch of people with all their possessions and transported them to Israel. We flew them into Tel Aviv and then returned to a standby status sailing off the coast of Italy. All of our aircraft were in an up status and we were scheduled for an amphibious landing in Spain in a few weeks. For the present, we could practice night externals with the CH-53D. The plan was to pick up a 105-millimeter howitzer off the stern of our flotilla Landing Ship Dock at night, fly a circle and then deposit it back on the same deck. The Squadron would maximize the available flight time by hot seating pilots. The aircraft carried a crew of two pilots, one crew chief and one gunner. They also carried two more sets of pilots for the hot seat operation. Each set of pilots picked up the howitzer and put it back on the shipís deck. Night externals appeared to be a success. When the drill was finished, the aircraft was going to take off and fly back to our ship. The aircraft departed the LSDís flight deck without a problem and then flew into the water. We lost 4 people in that crash and we didnít do any more night externals. Night vision capability didn't exist at that time. The purpose of the training was for a night amphibious landing that never happened.

A CH-46D couldnít land on the flight deck with one engine and a full load of troops. One engine didn't have the power to hover out of ground effect for a normal flight deck landing. One option was to clear the flight deck and try a run on landing. We didn't have any experienced doing that type of landing and we could have crashed on the flight deck killing everyone in the aircraft. A better plan was to land in the water next to the ship. The sea state was moderate, but not flat. The pilot executed a perfect run on landing about 200 yards off our port side. The pilot secured the rotor system and the troops exited the aircraft. Getting them safely into the water and then cutting them in half with the rotors wouldn't work. The pilot had to stop the rotor system. They had their life vest on when the aircraft landed and they departed the aircraft when the rotors stopped turning. After the rotors stopped, the aircraft became unstable and it slowly turned over and sank. Everyone was rescued without being hurt, but the Squadron had two aircraft at the bottom of the sea. This accident was caused by an engine that stopped running and couldnít be restarted. The Crew Chief didn't see anything physically wrong with the engine after it stopped. The cause of the engine failure was located with the aircraft at the bottom of the sea. We didn't know why the engine failed, but we suspected fuel starvation may have been the cause. Where was Sherlock Holmes when you needed him?

A CH-46D couldnít land on the flight deck with one engine and a full load of troops. One engine didn't have the power to hover out of ground effect for a normal flight deck landing. One option was to clear the flight deck and try a run on landing. We didn't have any experienced doing that type of landing and we could have crashed on the flight deck killing everyone in the aircraft. A better plan was to land in the water next to the ship. The sea state was moderate, but not flat. The pilot executed a perfect run on landing about 200 yards off our port side. The pilot secured the rotor system and the troops exited the aircraft. Getting them safely into the water and then cutting them in half with the rotors wouldn't work. The pilot had to stop the rotor system. They had their life vest on when the aircraft landed and they departed the aircraft when the rotors stopped turning. After the rotors stopped, the aircraft became unstable and it slowly turned over and sank. Everyone was rescued without being hurt, but the Squadron had two aircraft at the bottom of the sea. This accident was caused by an engine that stopped running and couldnít be restarted. The Crew Chief didn't see anything physically wrong with the engine after it stopped. The cause of the engine failure was located with the aircraft at the bottom of the sea. We didn't know why the engine failed, but we suspected fuel starvation may have been the cause. Where was Sherlock Holmes when you needed him?

Our aircraft flew most of the Squadron personnel back to New River. The ship pulled into the same dock where we departed 6 months before. Home looked real good. We had lost some good Marines on this cruise and we were not at war. This was not a good cruise from that standpoint. Marine helicopter aviation has always been a dangerous profession. Projecting this countryís interests throughout the world is what we do as Marines. In most cases, itís a Marine helicopter thatís going to cover the last leg of the journey to the enemy.

Our aircraft flew most of the Squadron personnel back to New River. The ship pulled into the same dock where we departed 6 months before. Home looked real good. We had lost some good Marines on this cruise and we were not at war. This was not a good cruise from that standpoint. Marine helicopter aviation has always been a dangerous profession. Projecting this countryís interests throughout the world is what we do as Marines. In most cases, itís a Marine helicopter thatís going to cover the last leg of the journey to the enemy.

![]() They were hiring new people to do the overhaul work on rotor blades and they were working on weekends. A new unsupervised mechanic had painted an overhauled spar with zinc chromate paint. He bonded the bladeís leading edge to the painted spar. The only thing holding the leading edge to spar was paint. When the pilot applied the rotor brake, the leading edge separated from the spar. The copilot released the rotor brake, advanced the engines to the fly position and tried to return to a flight condition that he had before he applied the rotor brake. The bad blade couldnít fly or spin without the leading edge and that blade cut the fuselage in half.

They were hiring new people to do the overhaul work on rotor blades and they were working on weekends. A new unsupervised mechanic had painted an overhauled spar with zinc chromate paint. He bonded the bladeís leading edge to the painted spar. The only thing holding the leading edge to spar was paint. When the pilot applied the rotor brake, the leading edge separated from the spar. The copilot released the rotor brake, advanced the engines to the fly position and tried to return to a flight condition that he had before he applied the rotor brake. The bad blade couldnít fly or spin without the leading edge and that blade cut the fuselage in half.

Itís less obvious that rebuilding all the CH-46 rotor blades in the Marine Crops and Navy inventory could cause an accident. Anytime maintenance activities change their routine for whatever reason; the possibility of error is going to increase. Good supervision is the only fool proof solution for the aberrations that are not routine maintenance. Someone has to manage the changes as they occur. A good Maintenance Officer with a mechanical background and some experienced Non Commission Officers are the primary means of accident prevention in most Marine Corps Squadrons. Mechanics and technicians that are well trained and motivated are the other part of the equation. People make the difference in aircraft maintenance.

Itís less obvious that rebuilding all the CH-46 rotor blades in the Marine Crops and Navy inventory could cause an accident. Anytime maintenance activities change their routine for whatever reason; the possibility of error is going to increase. Good supervision is the only fool proof solution for the aberrations that are not routine maintenance. Someone has to manage the changes as they occur. A good Maintenance Officer with a mechanical background and some experienced Non Commission Officers are the primary means of accident prevention in most Marine Corps Squadrons. Mechanics and technicians that are well trained and motivated are the other part of the equation. People make the difference in aircraft maintenance.